How Mary Hanson lost an arm, and cost Todmorden an arm and a leg

Dec 21, 2024

0

37

0

Just in time for Christmas, Local Studies brings you a tale of good deeds gone unrewarded, a distinct lack of human kindness, and Good Samaritan-ism coming back to haunt people. Who’s to say we aren’t festive folk in the library service? Never mind – the story here is of a stranger in a strange land whose accident and subsequent medical treatment caused a very local scandal in the 1880s. You might find some aspects of this story very relevant to today…but also, this story does involve some gruesome details, so don’t say we didn’t warn you.

The protagonist of this story is Mary Hanson. Little is known about Mary as a person (believe us, we tried). All we really know about her is what was reported in the coverage of her accident, court cases, and subsequent controversy over her legal representation, and even some of that is a little suspect. The census returns help us to get a little closer though. She was born in 1826 and for almost her entire life she lived with – maybe even was raised by – her spinster aunt Alice Hanson in Bingley, near Bradford. In 1851 Mary and two of her adult siblings were living with Alice, as well as Mary’s illegitimate son Joseph Smith Hanson. He had been born in 1847 at Bingley Workhouse, where Mary was staying at the time as a single pregnant woman.

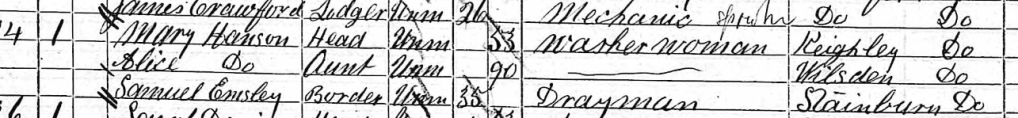

Mary, when she did work, worked as a power loom weaver which is unsurprising given her location and time. She continued to do so for decades afterwards. The last public record we can find of her before her accident is in Keighley in 1881, living at 34 Bedford Street with Alice and a boarder, drayman Samuel Emsley. Mary’s occupation is now washer woman and her birthplace is given as Keighley, which allows us to be certain of the identification given some of the details that emerged later. Being a washerwoman or charwoman was heavy, tiresome, and filthy work, and it was often undertaken by single women or widows who had few skills with which to find better paid or less onerous work. Poor Mary must have struggled.

The impressively long-lived Alice died in Bradford in 1885 at the age of 94, which perplexingly puts her demise well past the time when Mary’s “adventure” took place. So what sent Mary on her travels down towards Halifax, and then down the valley? We don’t know. But she did come down this way and apparently all on her own.

She found a placement at the Moorcock Inn in Hebden Bridge on Bridge Lanes, which had gone on for about a month before the accident, and had initially been lodging there with a man called Thomas Gallaghan who she called her husband. Thomas, according to the landlady, “stayed there all the time, and slept with her, going away in the afternoon, and she [Mary] followed him in the evening”. Mary had represented herself as a widow and as she was a hard worker and conscientious the landlady turned a blind eye to her partner and let her do her work in peace.

Thomas had found lodgings of his own at Marshall’s lodging house on the outskirts of Todmorden and on the fateful night of September 8th 1883 Mary was walking back from Hebden to Marshall’s to meet him and get to bed. She had been working all day and it was dark along the road. She had with her a small half-empty bottle of whiskey which she seems not to have touched, and which she later maintained had been a gift from another lodger which she had taken out of politeness.

At Callis, back then, there was no pavement on the side of the road and so no footpath on which pedestrians could safely walk. The canal would, of course, been filled with moorings, and wouldn’t have necessarily been the safest place for a lone woman to walk in the dark. There was a bend in the road, there was a tree overhanging at Dover Cottages (now Underbank), and Mary’s eyesight was bad. All these details are important because otherwise the accident makes little sense.

In the meantime Arthur Hollinrake, a driver for the Todmorden Carriage Company, had set off from the depot in Todmorden heading towards Charlestown with a number of passengers. He had asked his manager for some headlamps for the carriage before setting off but his manager said he’d be all right without them as it was still light. By Sandbeds, though, twilight had fallen. It wasn’t so dark though that Arthur didn’t see Mary as he turned the bend at Callis Bridge End, and not so dark that another pedestrian, Cockcroft Crowther, didn’t see Arthur and the carriage approaching.

Cockcroft called to Mary to look out. By some accounts she heard him and moved and by others (her own) she heard nothing. Arthur says that Mary moved out of the way but at the last minute veered back towards the centre of the road and was run over by the horses and the wheels of the carriage. Her left arm was crushed, her bag of food and supplies covered in blood, and several passengers leapt out and moved her first to one side of the road and then the other, all trying to staunch the flow of blood from her shoulder.

Arthur, faced with such a scene, left his passengers to handle things and kept going – after all, some of the other passengers had places to go and two of them in particular, ladies, said they would not ride if he took Mary onto the carriage. Their lack of sympathy (and the prospect of losing fares) spurred him on. He also, though, did not press when the company supervisor at Charlestown said not to bother with fetching a doctor, as then the expense would be on them. Reading between the lines an assumption was made that she was a drunken tramp (by all accounts she didn’t smell as clean as she could have smelt) and therefore the accident was her fault. It wasn’t until he arrived back in Todmorden that anyone took the idea seriously, but in the meantime a constable at Eastwood had sent for the workhouse doctor and she had been conveyed up to Stansfield View, where the following morning her left arm was amputated. Apparently the operation was performed using chloroform and antiseptic spray and she “bore it very well”…you shudder to think don’t you.

How does a one-armed woman do the laundry? Well, she doesn’t. And this was the problem now; a woman from outside the Union had been injured and needed emergency, expensive, medical care from the parish, as well as board and possible ongoing support costs. The question of “who’s financially responsible for this woman” was of course not going to be ascertained while she was bleeding out on the ground! So she was patched up as best she could and the question was then considered of what to do. Hearing her story and gathering information from the passengers who had stayed on, the Guardians decided to sue the Todmorden Carriage Company for costs. The chairman, Charles Crabtree, was said to have sworn to bear the costs himself if they could not get a settlement from the company – although this was not reported at the time and only became important later. There’s disagreement in the record about the settlement which was first proposed – reports ranged anywhere from £10 to £25 – but the Guardians ultimately refused a settlement on Mary’s behalf and the assistant Town Clerk, Samuel Camm, filed the legal papers.

Judge T.W. Snagge heard the case and he was unimpressed by arguments made by the solicitors for the Carriage Company, and ultimately ruled that the accident was avoidable and that Mary was entitled to compensation not just for her experience but for her future loss of earnings. His ruling hinged on the lack of headlamps and the inadequate explanation for why they had not been provided on the night as well as their lack of presence as standard on all carriages. If there had been lights then environmental factors like the oncoming evening and the curve in the road that hid the carriage from Mary’s view wouldn’t have contributed to the incident. He awarded Mary with £50 for her experience, a quite staggering for the time sum of money. His reasoning was that it would help her to set herself up in a business of her own. The Carriage Company had offered Mary some paid work as an alternative but given the choice she went with the lump sum.

The Carriage Company were understandably very unhappy about this and appealed. And at the appeal – held in December 1883 – the two justices sitting on the Court of the Queen’s Bench reversed the initial ruling and ruled out any chance of appeal on the Todmorden Board of Guardians’ behalf. Now they were on the hook for Mary’s medical costs as well as the Carriage Company’s appeal costs, and also the costs for Samuel Camm’s billable hours for both trials since they had instructed him on Mary’s behalf. Camm’s costs were for £75 and the Carriage Company subsequently submitted an invoice for an extra £32 17s 4d, bringing the total to just over £107. Merry Christmas indeed to the Board of Guardians!

1884 arrived and time marched on. Mary had been recuperating at the workhouse up on the tops – plenty of fresh air, some food, decent nursing and doctoring – and in March she told the doctor there that she was ready to leave and go back into the world. If she thought she’d be reunited with Thomas she was in for some bad news as he’d already left the area and gone to Bacup. But the Guardians decided not to release her yet, claiming that she was “as useful as a woman with two arms” and that she was assisting with looking after the older women there. They had the right to detain her, but their reasoning was suspect and one Guardian questioned their decision saying that they were keeping her “for another purpose”. What purpose though? That’s a question a set of petitioners, some of whom were on the Town Board (the pre-incorporation equivalent of today’s Town Council), decided to ask publicly. Was it a coincidence that around this time the Board of Guardians imposed a rule on local reporters that they could only report back on discussions which were subsequently included in the official minutes? Probably not. This was received by the newspapers precisely as happily as you might imagine, and editorials made it clear that if they were only allowed to report on the minutes that they wouldn’t bother wasting time attending meetings anymore. This threat doesn’t seem to have caused the Guardians to back down.

There had already been rumblings that steps ought to have been taken to determine who was legally chargeable for her stay and medical costs before embarking not just on legal action but on treating her at all. Seems heartless but remember that it was actual law of the land that paupers were chargeable to the parishes of their birth – intended to stop poor travelling people from putting burdensome costs onto either small parish areas or big cities. You could be more or less deported, aka “removed”, back to your chargeable parish if you became sick or impoverished in another part of the country. Mary’s lack of discharge from the workhouse and the increasingly hefty costs of the court cases had angered many on the Town Board who felt that ratepayers ought not to be responsible for her costs. All arguments we still hear today; “sure I feel sorry for them, but it’s not my responsibility to pay to help them out”.

Meanwhile Charles Crabtree, the chairman of the Guardians, had not endeared himself to his fellows or to some members of the public due to his strong stance on the question of Mary’s care and the lawsuit. Crabtree was a well-known man, the owner of Ferney Mill and a textiles business that had been in the family for generations, and had for many years been on the Board of Guardians and active in politics in the town. But the Hanson case had cost him a great deal of political capital and word began circulating that his position might not be secure any longer.

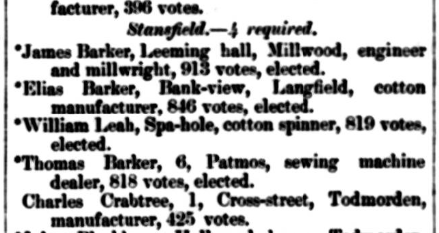

When the April 1884 local elections began to loom on the horizon he began to panic about the safety of his seat. The petition had, after all, been informed by someone or someones who also sat on the Board of Guardians, and Camm’s resignation as Assistant Town Clerk was being partially attributed to the case even though Camm repeatedly insisted that it wasn’t. So Crabtree made a risky move based on the law of probability: he resigned his seat on the Langfield Ward and stood for re-election in Stansfield Ward. This was because only two seats were up for election in Langfield (including his), but there were four seats up for election in Stansfield. Crabtree gambled in the hopes that his long service and position as a large employer would hold him in good electoral stead.

His gamble failed. Not only did he not win one of the four seats, his vote count was only just over half of the vote count for the lowest-ranking of the four men elected. Crabtree had paid the price for his strong defense of Mary’s litigation, but in a sense he dodged a bullet. Now Camm’s costs, and the Carriage Company’s costs, would have to be borne personally by the Board of Guardians, of which he was no longer a member. His political exile was a short one, so we don’t need to feel sorry for him. Crabtree would later be elected to the Local Board in 1886 and was a significant player in the push to ratify Todmorden’s Charter of Incorporation from 1889 all the way to its adoption in 1896.

Post-elections the Hebden Bridge Times printed a gossipy little item about Mary’s ongoing litigation costs and implied that disagreements among the Guardians were holding up payments as well.

Oh, delicious pickles indeed! The final – and unsigned – petition, which criticised their decision making from the time of injury, objected to the legal action as frivolous, and accused them of holding Mary against her will at further expense so they could possibly produce her as a witness in any further legal action, was submitted to the Board of Guardians in June 1884. They took time to consider their response.

Surprisingly, the Guardians hit back. In spite of Crabtree’s failure to defend his actions electorally and his subsequent absence from the board, and the bad publicity they had all received as a result of his influence and the decision to support Mary’s claim, their response is well in keeping with a town whose angry response to the 1834 Poor Law Act is still renowned. Mary was a “casual pauper” who could not be removed without cause; her accident legally paused any removal proceedings that could have taken place; it was within their right to keep Mary until she was fully recovered and able to travel safely to her parish of birth if they decided to remove her; it was right to take legal action to recover the costs of her care to protect the money they got from the ratepayers; and probably the most immediately obvious, it would have been unconscionable to try and move a woman whose arm had just been half torn off in an accident halfway across West Yorkshire or to stand there quibbling over her body while she bled in the road. Perhaps they phrased it a little more politely than that…but the read is clear.

The petition had also grumbled that the decision to take legal action had only been carried by a majority, not unanimously, and the Guardians again politely pointed out that local government did not operate in that manner at any level. Regardless of their private discussions, where they lamented not taking the time to “ask ourselves ‘are we responsible’…” before taking action, their official stance was that they had done the morally and legally correct thing even if there were regrettable elements to the situation.

One last loose thread remained to be tied up; they would still need the Local Government Board’s permission to settle Camm’s bill for £75 and the Carriage Company’s bill for £32. Of course, that permission never came…and the Guardians could not even fall back upon their former chairman’s promise to pay it out of his own pocket if need be as he was no longer in office and the verbal contract was apparently unenforceable. The record is silent about where the money came from but presumably either Crabtree or the Board members stumped up out of their own pockets to avoid further drama. As far as public record is concerned that was the end of that. The solution must not have made it into the official minutes.

And what of Mary’s fate? We have no idea. As we said before, nonagenarian aunt Alice died in 1885 and Mary’s son Joseph Smith Hanson died in 1889. We’ve searched the BMD index to try and find any deaths that could be hers, cross-referencing them with newspaper reports from those areas, and can’t pin down any particular Mary as definitely being her. So we have to end her adventure here. Where she ended up and how well she managed for the rest of her life with only one arm is anyone’s guess. She may have common-law married another man later, or gone by an assumed name, and on her death no one knew better enough to make sure her birth name was the one it was registered under. Stranger things have happened. Stranger things happened to her!

Her story is a universal one though: the story of a stranger who needs help, of the people who gave that help, and of the tensions that exist between the moral impulse to do what’s right and the consequences (financial or otherwise) of doing what’s right. We’re still having these conversations – sometimes arguments – today and probably always will. Merry Christmas indeed.